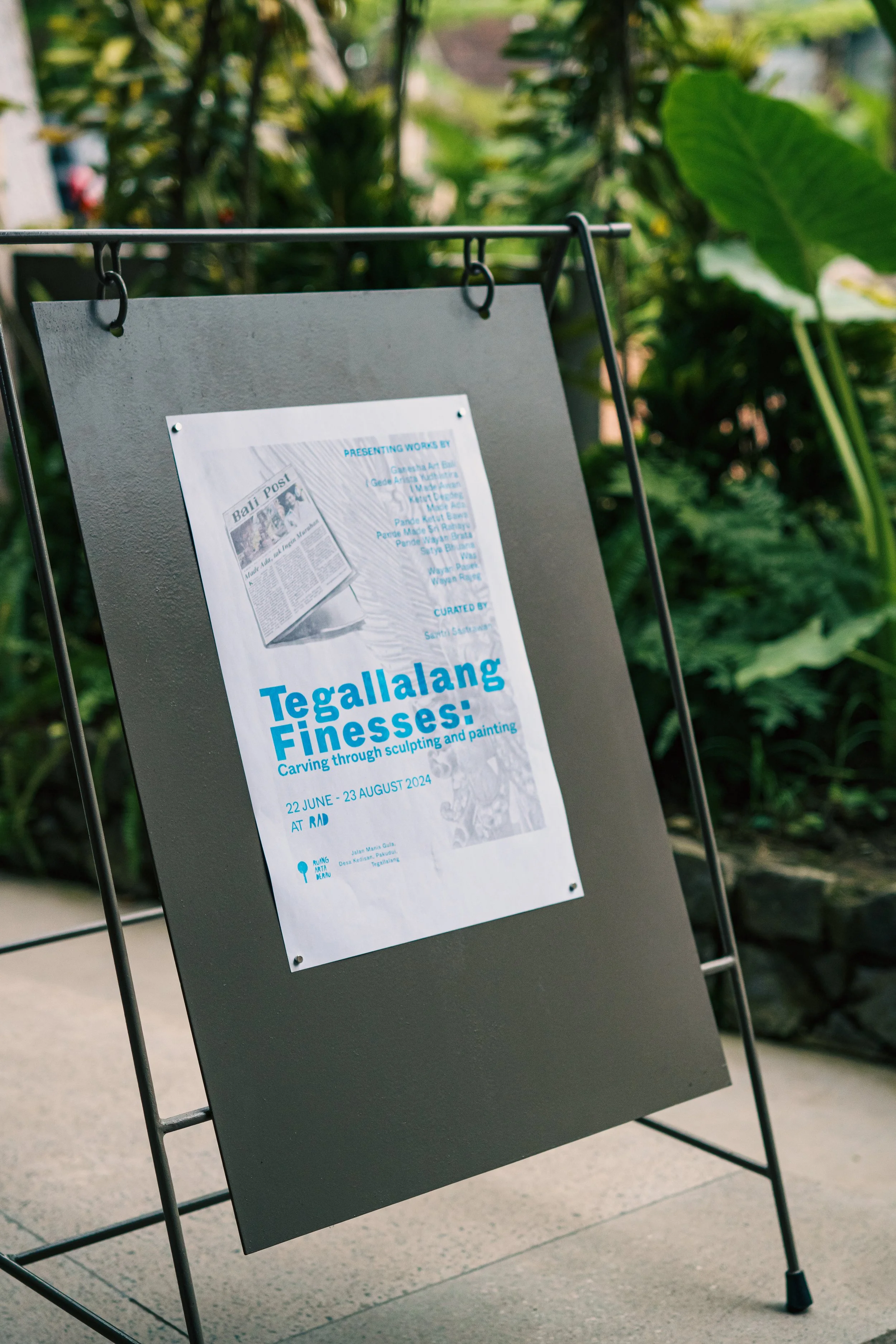

Tegallalang Finesses: A Portrait of Local Legacy

Ubud isn’t Tegallalang. It never was.

And while that may seem like a trivial geographic clarification to some, in the world of Balinese art, it’s a line that matters. For decades, Ubud has basked in the spotlight, shaping the narrative of what “Balinese art” means to the wider world. But Tegallalang? It’s often been boxed into a different category, like wood crafts, souvenir shops, touristy rice terraces. Beautiful, sure. But not exactly where people go to hunt for bold artistic statements or whispers of radical local expressions. At least, until Tegallalang Finesses happened.

MAPPING WHAT MATTERS

Tegallalang Finesses was the only project in 2024 that Ruang Arta Derau (RAD) commissioned with a dedicated research phase. Since November 2023, we’ve been actively researching the essence of Tegallalang art and its significant contributions to the daily life of its residents—ranging from painting to sculpture. And the researcher is Savitri Sastrawan, who also curated the exhibition. As a daughter of a diplomat, she grew up moving from country to country, always carrying bits of Bali in her suitcase, especially when her family was stationed in London and Zimbabwe. Now married to a deeply-rooted Balinese artist, Npaaw, Savitri’s journey circled back to her own cultural roots. And what she brought to the table was personal yet layered.

The term Tegallalang Finesses itself was coined by Savitri. There was something beyond intelectual in how she noticed the gap in how we talk about art in this area—minimal documentation, few platforms, and too many assumptions. What she uncovered during her qualitative research was a pattern of persistence. Local masters and maestros—still working, still carving, still painting—with no proper narrative to wrap their lifelong dedication. This wasn’t about inventing prestige. It was about finally paying attention.

One key figure emerged during the research: Satya Bhuana. A native of Ceking, Satya is practically a walking embodiment of multidisciplinary culture. Dalang, Balinese dancer, architect, urban planner, barista, folk singer, painter, grandson of an undagi (Balinese architect)—he’s not just involved in the arts, he breathes it. As chairman of Karang Taruna Tegallalang, Satya became Savitri’s main informant, as he proved to be more than reliable and capable in bringing deep knowledge of the carving world, as he himself is coming from a family full of sculpture artists.

Satya Bhuana with his grandfather, Ketut Degdeg, and his final sculpture behind him.

Satya wasn’t just sharing stories. He was mapping oral histories passed down through his family, adding details that never made it into books or exhibitions. One anecdote he shared is about the Garuda shape. According to Satya, it was originally made in a sitting position. However, over time it became in a standing position, as we generally find now (especially from the biggest one, Garuda Wisnu Kencana in Jimbaran by Nyoman Nuarta).

Through Satya, Savitri was able to trace not only specific artists and their legacies, but also the cultural infrastructures whether it’s formal or informal that support them. From these insights, she made curatorial decisions based not on style or trend, but on artistic consistency and significance within Tegallalang itself.

And the result is a roster of artists who represent more than technique or tradition. They represent longevity. Commitment. And that stubborn Balinese tendency to keep creating, even when no one is watching.

Carving, Not Just Wood—but Identity

Let’s start with something familiar. One of the most culturally loaded objects in the Indonesian diaspora is the Garuda sculpture. As a diplomat’s kid, Savitri saw these majestic creatures everywhere, like in the embassies, consulates, and state buildings. But few people know that many of those pieces were made in Pakudui, a small banjar in—you guessed it—Tegallalang.

Here, the making of Garuda statues is more than tradition—it’s a full-fledged cultural industry, rooted in inheritance, refined through labor, and shaped by the rhythms of tourism and state demand. Families in Pakudui have been carving for generations, often in communal workshops where skills are taught informally but rigorously. The process is both collective and deeply personal. These artisans aren’t just producing souvenirs or decorative icons—they’re literally carving the symbols of Indonesia’s imagined self. Yet, as Savitri points out, while these works occupy national and international spaces, the hands that create them are rarely acknowledged in the same spotlight.

Garuda and Jatayu in various representation (top, left-right: Indonesian Embassy in Harare, Indonesian Embassy in The Hague; bottom, left-right: Indonesian Embassy in London, Indonesian Embassy in New Delhi)

Take, for example, Wayan Rajeg, one of the local artists featured in the study. While he continues to sculpt Garuda Vishnu and lions—long-standing icons of Balinese and national identity—he has also responded to shifting markets and the demands of global tourism. Over the past ten years, he’s been working on sculptures based on Christian religious motifs and European mythological stories, catering to both church commissions and curious foreign collectors. Executed in a distinctly European classical style, these works expand the scope of what “Balinese wood carving” can mean, demonstrating the adaptability and range of the artisans. This shows how traditional art can connect with changing stories, blending local and global, sacred and everyday influences..

In her writing, Savitri resists romanticizing this craft. She doesn’t flatten the practice into simple heritage or pure devotion. Savitri’s perspective is sociological, but she never makes it feel too academic. She takes a more practical and realistic approach. She reveals how economic necessity, tourism dependency, and aesthetic expectations from both domestic and foreign customers would influence what gets made and how. She observes how artistry and entrepreneurship coexist in complex ways, and how global visibility can paradoxically erase local names even as it elevates their products. Carving, in this context, becomes a quiet but insistent negotiation with power: who gets to be seen, who gets named, and who gets remembered.

An Exhibition that Tells Stories

From June 22nd until August 23rd, 2024, the walls of RAD were hung with wood sculptures, wood masks, and paintings. Works weren’t grouped by artist or theme, but laid out like an ongoing conversation: open to interpretation. Adding to this sense of lived history were old newspaper clippings featuring the artists—reminders of past recognition that still matter today. Along with early sketches and drawings, they served as records and quiet proof of the artists’ daily lives and long careers.

One of several retrospectives featured in the Tegallalang Finesses exhibition.

Each piece came from a place of practice rather than presentation. Artists like I Gede Arista Yudhistira, I Made Awan, Ketut Degdeg, Made Ada, Pande Ketut Bawa, Pande Made Sri Rahayu, Pande Wayan Brata, Satya Bhuana, Was, Wayan Pasek, and Wayan Rajeg shared works that reflected their daily realities. Some were established names with decades of experience; others were younger practitioners still rooted in their family workshops. Their techniques were inherited, practiced, repeated, and refined.

The exhibition didn’t aim to declare a movement or to signal some grand rediscovery. What it did was hold space. A space where someone like Satya Bhuana could stand next to the creations of his grandfather’s. A space where repetition became revelation: a daily sketch, a carved wood panel, a rough painting that might never have left the studio. The kind of things that don’t scream for attention but speak volumes when given the chance.

As an independent art space based in Bali, RAD is committed to supporting local artists and creative communities. It focuses on the artistic process as much as the final product, making it a space where artists can show their work in an honest and unfiltered way. Exhibitions at RAD are not about meeting external expectations or following trends—they're about presenting the work as it is, in its own context. This makes RAD especially relevant for artists in Tegallalang, whose practices are rooted in long-standing traditions and everyday realities.

The contrast between RAD’s modern, industrial-style architecture and the traditional, handcrafted works on display creates a visual contrast that highlights the value of both worlds. It allows the artworks to stand out while subtly reminding visitors of the broader changes surrounding Bali’s art and craft culture. It is truly a cool collision—where concrete meets carving, and past meets present without either one getting lost.

Let’s Talk About Demand

Here’s the thing: tradition doesn’t survive on nostalgia alone.

One of the most refreshingly honest takes Savitri brings to the table is her unwillingness to romanticize the scene. Yes, there’s heritage. Yes, there’s community. But without commercial demand, without buyers, collectors, or even curious tourists, a lot of this collapses. Not because the artists stop creating—but because the infrastructure around them is almost nonexistent.

Support systems in the Indonesian contemporary art world are fragmented at best, many talented artists work in the shadows—locally known, globally invisible. And while Tegallalang is rich in craft and spirit, it’s poor in resources, platforms, and sustained backing.

That’s why practical views matter. Art doesn’t happen in a vacuum—it needs room to grow, tools to evolve, and systems that actually work. One telling example is the anecdote Savitri wrote about Wayan Gede Mancanegara, better known as Yande. In 2018, he received a large-scale commission to produce 1,000 Garuda sculptures as souvenirs for an IMF event. The job came to him through a government channel—an opportunity that originally would’ve gone to his father, a long-established figure in the carving world. Yande took it on, navigating the challenges of coordinating dozens of sculptors, managing materials like resin alongside traditional wood, and scaling up production without losing quality.

That commission didn’t just bring exposure—it created jobs, sparked innovation, and helped Yande launch Ganesha Art Bali, a shop he continues to run in Pakudui and which also participated in Tegallalang Finesses. It’s a vivid example of what happens when the right kind of support meets the right kind of talent: artists and artistry aren’t just sustained, they grow.

Savitri’s conclusion doesn’t shy away from this: commercial viability plays a vital role in preserving what we love to call “authentic” or “local.” Romantic ideas don’t pay rent. And while discourse and theory are important, sometimes what matters more is: can the artist keep making?

So Why Does This Matter?

This particular project is needed because giving space to artists in Tegallalang isn’t about romanticizing tradition or offering charity—it’s about restoring accuracy. These creators aren’t hidden gems waiting to be discovered; they’ve always been here, working with silence resilience. Places like RAD help make that visible. RAD gives these artists room to show their work as it is, without having to explain or adjust themselves to fit outside expectations.

Also, acknowledging the role of commerce in this equation doesn’t mean compromising authenticity. It means recognizing what it takes to survive, to sustain, and to keep going when systems don’t always show up for you. In a world obsessed with novelty and noise, maybe what we truly need is to slow down and sit with what’s already been here: the lasting, the grounded, the unapologetically local.

And perhaps, finesse doesn’t always come dressed in polish or prestige. Sometimes, it shows up as sheer persistence—the kind that keeps carving, painting, and creating, simply because of the love for the arts itself.